Ilse D’Hollander, a film by Gautier Deblonde

Shot on location in Paulatem, Ilse D’Hollander’s home between 1995 and 1997, Galerie In Den Bouw, Kalken, the venue of the artist’s first and only solo exhibition during her lifetime, and the Zwalm countryside, summer 2018, this film by Gautier Deblonde was produced on the occasion of the first solo exhibition in the UK of works by the late Belgian artist at Victoria Miro Mayfair. It features a rare text written by the artist, read by the Belgian actor Francesca Vanthielen.

About Ilse D’Hollander

In her short life, Ilse D’Hollander (1968–1997) created an intelligent, sensual and highly resonant body of work. Born in Sint-Niklaas, Belgium, in 1968, graduating from the Hoger Instituut voor Beeldende Kunsten, St Lucas, Gent, in 1991, D’Hollander was steadfastly committed to painting as an intellectual and emotional endeavour. Her often small-scale canvases and works on paper are charged with references to the everyday. Yet, enlivened by an expressive, though always economical, touch, her work resonates just as strongly as a sustained, self-reflexive enquiry into the act of painting: what it might take to bring an image into being on a bounded, flat plane.

An extract of Silent Songs by David Anfam

Published on the occasion of the first exhibition of the late Belgian artist in the UK, Silent Songs, by David Anfam, writer, critic and Senior Consulting Curator at the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, considers the rich dialogue between abstraction and representation in D’Hollander’s art.

'…D’Hollander’s art reflects a twofold gaze: one eye, so to speak, scrutinised reality while the other sought to abstract it according to an inward or more spiritual axis. Time quickened this process. Early on, D’Hollander spoke with emotive prescience of never growing old enough to paint all the works she had in her head. To wit, ars longa, vita brevis.

D’Hollander’s native country, Belgium, exerted a sway over her vision. Its quietly ordered landscape, grey skies, pale or misty light (touched, as her brushmarks often were, with a soft opalescence) and the geometries formed by the interplay of straight canals, neat fields and upright/spreading trees echo through the oeuvre. In this respect, she upheld a lineage as venerable as Dutch landscape painting of the Golden Age and as modern as Piet Mondrian’s sparse compositions. Indeed, trees, their branches and trunks constitute leitmotifs in D’Hollander’s iconography.

By no coincidence, a series depicting trees that stressed their angularity marked a crucial waystage (1911-13) in Mondrian’s path away from the direct rendition of nature and towards non-objectivity. D’Hollander’s counterparts resemble revenants sprung from this genealogy after painting’s much-exaggerated death late in the last century that ultimately ended modernism’s forward march, a course begun by Mondrian and his avant-garde cohort during the First World War period. This reciprocity over time helps explain their haunting presence, as of things that at once are and are not themselves, skeletal monuments to a painterly medium redivivus. (The metaphor of art as a tree has a distinguished Romantic-cum-modern pedigree.Furthermore, when viewing the paintings in D’Hollander’s Estate earlier this year, a network of branches/lineation aligned exactly yet fortuitously with a crack in the room’s wall, as though attesting to a seamless, if occulted, link between art and life).

This essay is published in full in the exhibition catalogue.

Images from top:

Sun Dial / Zonnewijzer, 1996

Oil on canvas

53 x 46 cm

20 7/8 x 18 1/8 in

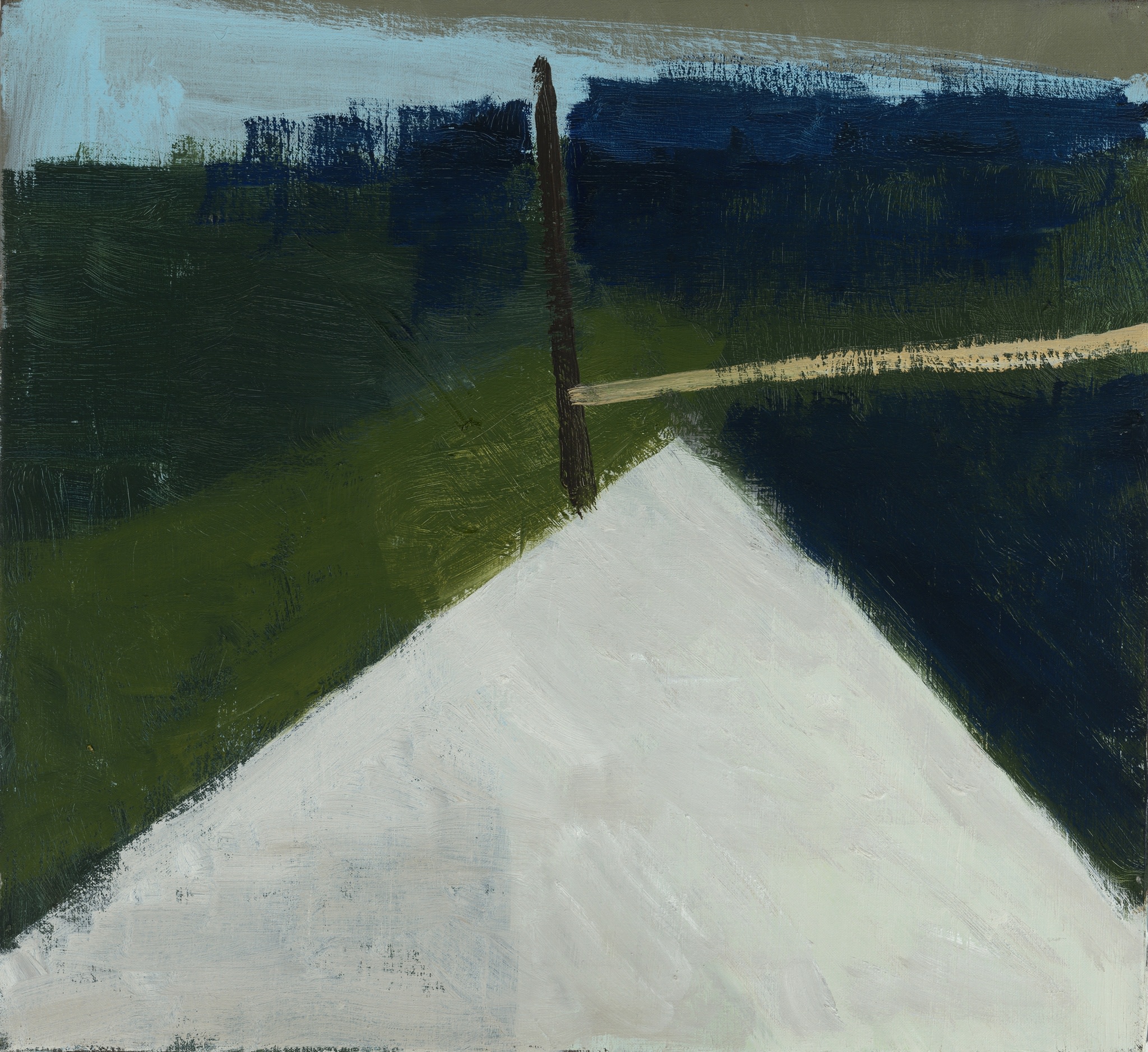

Untitled, 1995

Oil on canvas

35 x 38 cm

13 3/4 x 15 in

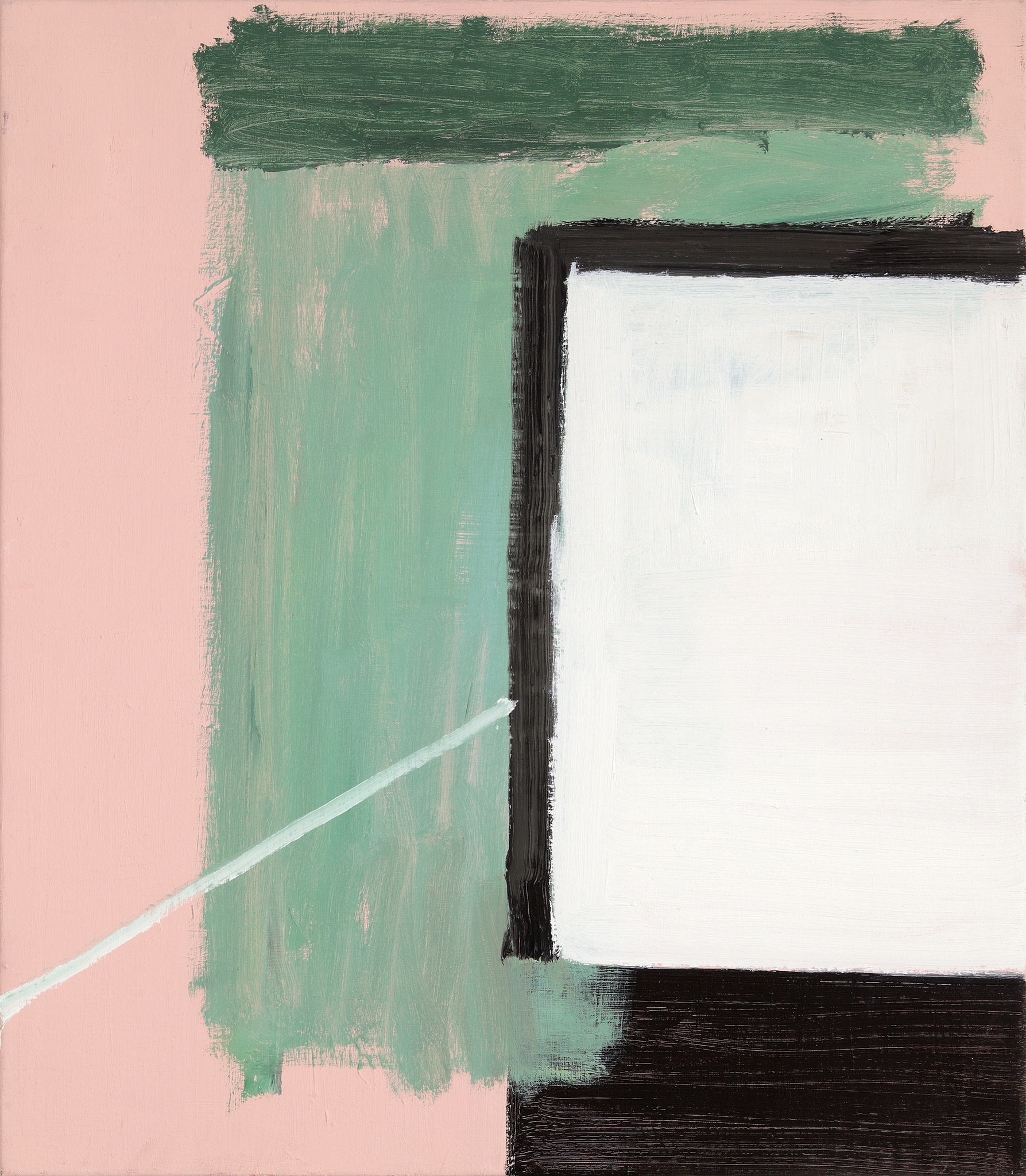

Untitled, 1996

Oil on canvas

62 x 55 cm

24 3/8 x 21 5/8 in

Untitled, 1996

Oil on canvas

70 x 70 cm

27 1/2 x 27 1/2 in

All works © The Estate of Ilse D'Hollander

Courtesy The Estate of Ilse D'Hollander and Victoria Miro