House Work

Including Mamma Andersson, Jules de Balincourt, Hernan Bas, Marc Chagall, Peter Doig, Adrian Ghenie, David Harrison, Karen Kilimnik, John Kørner, LS Lowry, Alice Neel, Celia Paul, Grayson Perry, Tal R, David Rayson, George Shaw and Cy Twombly.

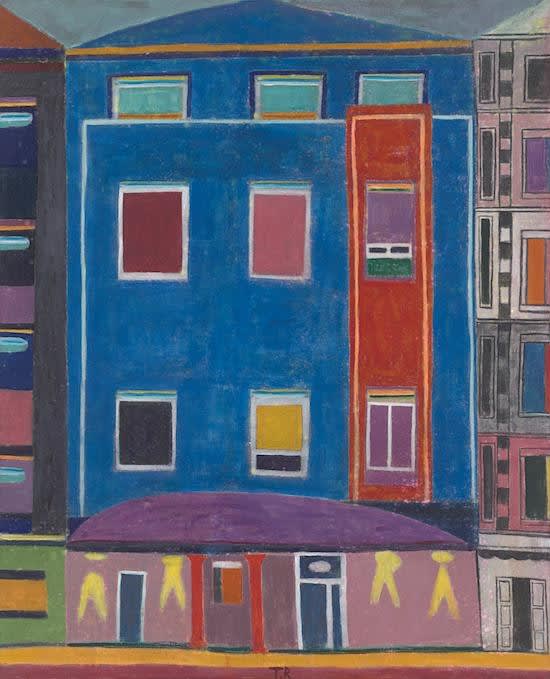

A group exhibition of contemporary and historical paintings looks at ideas of home from the perspective of artists working from the 1920s to the present. Featuring gallery and invited artists, and with a focus on depictions of houses and other dwelling places, House Work reflects a diversity of physical structures - from lone houses surrounded by nature, to buildings in urban and suburban settings. Equally, the exhibition gives rise to thoughts of home as a social construct, idea or state of mind.

Drawn from life, memory, imagination, or from sources such as films, books, newspapers and magazines, the works in the exhibition reveal a variety of human presences and traces of activity. From childhood homes, to holiday homes, haunted houses to dream homes, works tease apart the idea of the house as a place not only of physical shelter but also one in which to fix or locate particular memories or states of being. Houses that may appear magnified, miniaturised, condensed or fragmented inspire thoughts of home as a place of rootedness, safety, or privacy, the house as a sense of hope, or loss, as a territory to be defended, a place to escape to (or from), or one through which we seek to define ourselves in relation to others.

Completed in 1935, Alice Neel’s Belmar, New Jersey depicts, among others, the house rented by Neel on the New Jersey shore, in which she spent the summer of 1934 accompanied by her parents and, on a rare visit from Cuba – where she had been taken by Neel’s estranged husband – her daughter, Isabetta. Painted in her characteristically direct manner, Neel’s painting gives little away about the sadness and turbulence of her life during the period but exerts an uneasy calm. Pigeon House, 2010, by Karin Mamma Andersson shifts our focus to an interior where, seated at a table, three figures appear caught up in their own private worlds. Inspired by filmic imagery, theatre sets and period interiors, Andersson’s paintings are often dreamlike and expressive. Here, her evocative use of pictorial space and juxtaposition of opaque and translucent oil and acrylic paint hints at fragmented narratives and unresolved tensions between shared interiors and inner lives.

Peter Doig’s oil on paper work Untitled (Kricket), 1999, shares a sense of ambiguity. An apparently neglected house with blacked out windows is dwarfed by a pool that dominates the lower half of the image: more like a sink hole than a swimming pool or garden pond, this void serves to heighten a sense of uncertainty and accentuates a psychological dimension. A swimming pool, this time apparently well maintained and surrounded by people, similarly dominates the foreground of Jules de Balincourt’s Valley Pool Party, 2016, one of a number of paintings completed by the artist on his return to his hometown of Los Angeles after a twenty-year interval. Through transparent washes and saturated colours, de Balincourt conjures the unmistakeable vibrant landscape of California that feels familiar yet somehow compressed and over-saturated. Shaped by the vagaries of memory and imagination rather than directly from life, the work occupies a distinct emotional hyperspace. Memory also partly informs Celia Paul’s My First Home, 2016, a painting of the house in which the artist was born, in Trivandrum, India.

Throughout her career, Karen Kilimnik has questioned chronology and disrupted time, drawing upon historical precedence while replaying history through ornate frames of reference and counter reference. In The summer house of Apollo in the French countryside outside of Paris, 2016, first shown as part of the artist’s exhibition at Château de Malmaison in 2016, Kilimnik paints a historical view of the rear façade of the former home of Empress Joséphine that appears to exist between realms of fact, fiction, fantasy and illusion. Hernan Bas’ practice has always been intrinsically linked to an exploration of literature and the written word. In Preferring the out to the indoor night, 2010, a young man, his back turned to a number of wooden buildings, is engrossed in a book, apparently oblivious to his surroundings and the full moon that illuminates the scene. Fractured planes and tilted perspectives further add to the charged, mysterious atmosphere of an image where darkness and light, the known and unknown coexist and the lone figure seems poised on a threshold between the everyday world and the, perhaps yearned for, outer reaches of the poetic imagination. In David Harrison’s Moondrop, 2006, the solid forms of urban daytime cede to the thrilling ambiguities of moonlit night, drawing viewers into a space of enchantment, mutability, potential and, perhaps, joyous transgression.

The exhibition coincides with the gallery’s first exhibition of works by Do Ho Suh, at Wharf Road (1 February – 18 March 2017). Inspired by his peripatetic life Suh has long ruminated on the idea of home as both a physical structure and a lived experience, the boundaries of identity and the connection between the individual and the group across global cultures. The exhibition at Victoria Miro Mayfair offers a counterpoint to Suh’s work while further revealing houses and homes as subjects with enduring relevance and potential.

-

House Work reviewed in The Quietus

February 25 2017By Victoria Rodrigues O'Donnell House Work almost entirely features drawings and paintings. On display at Victoria Miro Mayfair, this is also a group exhibition that...Read More -

House Work reviewed in Time Out

February 13 2017See what they did with the title? House. Work. It’s a bit like ‘housework’, except it’s in two parts, which is very clever, because it...Read More

-

House Work is featured in the Guardian

February 8 2017The booby-trapped bedroom, the mysterious mincing machine, the body under the patio … why the sudden spate of shows taking a creepy view of home...Read More -

Martin Gayford reviews House Work in The Spectator

February 3 2017…Home — though not in a way that has much to do with Bloomsbury linen chests — is also the theme of House Work ,...Read More