Celia Paul: Desdemona for Hilton by Celia

New and recent works by Celia Paul draw on the artist’s delicate and moving explorations of intimacy with people and landscape. Since her first solo exhibition at Victoria Miro in 2014, there has been an increased focus on self-portraiture and seascapes. For this exhibition, examples from both bodies of work offer touchstones for thoughts about time, transience, spirituality and mortality.

Paul has produced a large number of evocative self-portraits over the course of her career. In these new works, she sits with her hands in her lap rather than with brush in hand, as if she were one of her own sitters. While her head and shoulders are painted with delicate free brushstrokes and possess an otherworldly quality, the clothes she wears, by contrast, are described with thick impasto. The paintings open up a painterly and conceptual dialogue between the dual role of subject and artist – caught between self-possession and self-scrutiny – as well as offering an extended consideration of the essential dualities of the medium – its ability to capture qualities of form, light and atmosphere, and its material presence.

-

Celia Paul and Paula Rego feature in London Calling at Kunstmuseum den Haag

February 14 2026The exhibition (14 February–7 June 2026), the first major survey of its kind in the Netherlands, brings together highlights of postwar British figurative painting. Read...Read More -

The Woman Question 1550–2025 featuring Celia Paul, on view at Museum of Modern Art Warsaw

November 21 2025Organised by curator and art historian Alison M. Gingeras, this exhibition (21 November 2025–3 May 2026) challenges the notion that women were largely absent from...Read More -

A painting by Celia Paul is installed in Chiesa di san Raffaele Arcangelo, Pozzuoli, as part of Panorama

September 10 2025Celia Paul's painting Madonna and Child and The Fire , 2025, is on view 10–14 September 2025 as part of Panorama , a city-wide exhibition...Read More -

Celia Paul on A brush with…

April 2 2025'I was thinking about what the paintings would look like when there was nobody in the gallery to see them. I think there is a...Read More -

Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts is reviewed by Observer

March 31 2025'She is deeply focused, delving inward as if mining the soul. This cannot be easy, finding such an elusive essence; yet somehow, in all her paintings, even the chair and the bed, there is this ephemeral, hovering essence.'Read More -

Celia Paul’s essay Painting Myself features in The New York Review of Books

March 13 2025'My recent self-portraits... owe their success to the power of my defiance. "I am a survivor," they are clearly saying. I am self-enclosed, as if the paint were my armour.'Read More -

Celia Paul talks to Charlotte Higgins for The Guardian ahead of her new exhibition, Colony of Ghosts

March 10 2025'Lucian died in 2011. I hadn’t felt inhibited by him. But I think I must have been, because it was at that point I thought, “I really need to change my life.”'Read More -

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s essay on Celia Paul features in The New Yorker

January 27 2025'...it is the paintings that I remember, and the feelings they left in me. Of course this is so, because they depicted presence — of the past, of the painter, of the tree — and what you have once been close to stays with you.'Read More -

Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood, featuring Chantal Joffe, Wangechi Mutu, Celia Paul and Paula Rego, on view at Arnolfini, Bristol

March 9 2024Hayward Gallery Touring’s major group exhibition (9 March–26 May 2024) explores lived experience of motherhood through over 100 artworks. ★★★★★ Reviewing the exhibition in The...Read More -

Celia Paul speaks with Beatrice Hodgkin for the Financial Times

October 25 2023‘It’s kind of, you know, the erosion of yourself, and the buildings. And yet there’s a quality of stillness. Which is actually what beauty is...Read More -

On view in Cambridge: Real Families: Stories of Change, featuring Chantal Joffe, Alice Neel, Celia Paul, Grayson Perry and Paula Rego

October 5 2023Bringing together more than 120 artworks spanning painting, photography, sculpture and film, the exhibition (6 October 2023–7 January 2024) asks us to consider what makes...Read More -

Pictus Porrectus: Reconsidering the Full-Length Portrait featuring Celia Paul is reviewed by Vogue

July 15 2022‘A new generation of artists, who are now basically the establishment, were coming up and interrogating all of these prohibitions around portraiture...’ – Alison M....Read More -

Celia Paul features in Pictus Porrectus: Reconsidering the Full-Length Portrait, curated by Dodie Kazanjian and Alison Gingeras

June 20 2022Pictus Porrectus: Reconsidering the Full-Length Portrait , curated by Dodie Kazanjian and Alison Gingeras, takes place at Isaac Bell House, Newport, Rhode Island, 1 July–2...Read More -

Studio International reviews Celia Paul: Memory and Desire

May 6 2022'At Victoria Miro, a more diffuse and dappled light permeates the upper gallery and I begin to feel that I am in the presence of...Read More -

Celia Paul Letters to Gwen John is reviewed by The New York Times

April 27 2022'For Paul, looking back in order to look forward, the artist who leaps across time is Gwen John — who was herself Auguste Rodin’s muse....Read More -

Celia Paul: Letters to Gwen John is reviewed by The Telegraph

April 5 2022'The end result is a beguiling, singular work of art – a portrait of two lives, entwined through time and space...' – Lucy Scholes Lucy...Read More -

Celia Paul is interviewed by Rachel Campbell-Johnston in The Times

April 5 2022'I hate the description 'artist in her own right',' Paul says. 'It suggests that we are still bound to our overshadowed lives… I hate the...Read More -

As reported by The Guardian, the National Portrait Gallery boosts female representation with self-portraits by artists including Celia Paul

March 8 2022The National Portrait Gallery has acquired five self-portraits by female artists as part of a three-year project to enhance the representation of women in its...Read More -

Jackie Wullschläger reviews Celia Paul: My Studio in the Financial Times

July 8 2020'How curious that in lockdown this inward-gazing painter looked outward to supreme effect; how magnificent that she celebrates in the physicality of paint a symbol of the virtual connections which kept us united. Her towers stand as lyrical odes to lockdown London.'Read More -

Martin Gayford writes about Celia Paul in The Spectator

December 12 2019Celia Paul is a living painter who is just, at the age of 60, beginning to get the attention she deserves. Her exhibition at Victoria...Read More -

The new Rubell Museum features works by Celia Paul and Hernan Bas

December 4 2019Opening on 4 December 2019 the new Rubell Museum features a museum-wide installation of works that chronicle key artists, moments, and movements over the past...Read More -

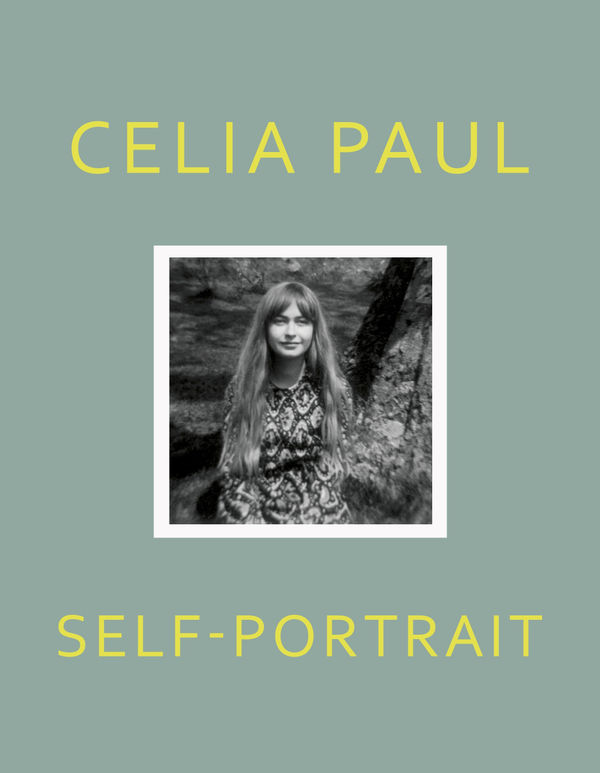

Celia Paul’s Self-Portrait is featured in The Times’ best art books of the year

December 1 2019 Read More -

Frieze reviews Celia Paul: Self-Portrait

November 26 2019In the artist’s frank new memoir, her turbulent decade-long relationship with Lucian Freud is one trial of many to be endured in the pursuit of...Read More -

Book of the week: The Guardian reviews Celia Paul’s Self-Portrait

November 20 2019The artist Celia Paul, increasingly frustrated by frequent mentions of her turbulent relationship in books and articles, decided to tell her own revealing story By...Read More -

Time Out reviews Celia Paul

November 19 2019★★★★ When you think of Celia Paul, you think of blue. Which isn’t entirely fair. Her paintings aren’t predominantly blue, but somehow ‘blue’ is the...Read More -

Anatomy of an artwork: Celia Paul’s My Sisters in Mourning in The Guardian

November 15 2019Celia Paul’s My Sisters in Mourning: a meditative portrait of a mother's death In this intimate depiction of her family, the artist paints with a...Read More -

Rachel Cusk profiles Celia Paul for The New York Times

November 7 2019'Can a woman artist – however virtuosic and talented, however disciplined – ever attain a fundamental freedom from the fact of her own womanhood?' Read...Read More -

Zadie Smith: The Muse at Her Easel, a consideration of Celia Paul’s memoir, Self-Portrait, in the New York Review of Books

November 2 2019The word museography properly refers to the systematic description of objects in museums, but it might also do for the culture and ideology surrounding that...Read More -

Celia Paul is awarded Harper’s Bazaar Artist of the Year

October 30 2019Harper’s Bazaar Women of the Year Awards recognises the outstanding achievements of women in the worlds of fashion, film, art, music, philanthropy and literature. Celia...Read More -

Celia Paul is interviewed by Tim Adams in the Observer

October 27 2019You walk up many flights of stairs to reach Celia Paul’s flat, but the climb is worth it. The windows of her studio and bedroom...Read More -

Celia Paul at The Huntington

February 9 2019Travelling from the Yale Center for British Art, the exhibition (9 February–8 July 2019) is curated by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Hilton Als and features work...Read More -

Celia Paul, curated by Hilton Als, at the Yale Center for British Art

April 3 20183 April–12 August 2018 The Center will present an exhibition of work by the contemporary British artist Celia Paul (b. 1959) in spring 2018, the...Read More -

Celia Paul writes in the FT about painting from life – and loss

March 16 2018Soon after my father died in 1983 I did a painting of my four sisters with my mother in the centre. I decided that I...Read More -

Tim Adams selects Celia Paul’s Painter and Model as one of his highlights of All Too Human at Tate Britain

March 4 2018Taught by Lucian Freud at the Slade, and for a time his muse and lover, Celia Paul made this self-portrait partly to subvert the familiar...Read More -

Celia Paul in All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life at Tate Britain

March 4 201828 February – 27 August 2018 Capturing the sensuous, immediate and intense experience of life in paint Celebrating painters in Britain who found new ways...Read More -

Ahead of the exhibition All Too Human at Tate Britain, Kate Paul discusses the experience of sitting for her sister, Celia

February 3 2018Interview by Rebecca Nicholson I’m the one lying down with my head on the pillow. It’s not often that I have such a comfy position....Read More -

The Art Newspaper reports on Celia Paul’s forthcoming exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art

August 4 2017Anglo(art)phile Hilton Als to organise series of contemporary shows at the Yale Center for British Art. By Victoria Stapley-Brown “I became interested in British art...Read More -

Last chance to see Celia Paul: Desdemona for Hilton by Celia

October 19 2016Celia Paul's solo exhibition at Victoria Miro Mayfair closes on Saturday 29 October. Paul’s art stems from a deep connection with subject matter. The works...Read More -

Celia Paul: Desdemona for Hilton by Celia reviewed by Studio International

October 13 2016In an exhibition dominated by self-portraits and seascapes, Celia Paul demonstrates the virtues of subtlety and perseverance. By Joe Lloyd Three self-portraits, a painting of...Read More -

Celia Paul creates an exclusive cover for the fourth annual edition of Bazaar Art

October 6 2016The fourth annual edition of Bazaar Art – distributed free with our November issue, on sale from 4 October – features six exclusive covers created...Read More -

Celia Paul: Desdemona for Hilton by Celia one of Harper's Bazaar's best Frieze Week events

September 29 2016With their themes of intimacy and isolation, the works on display at Celia Paul's new solo show at Victoria Miro, 'Desdemona for Celia by Hilton',...Read More -

Celia Paul: Desdemona for Hilton by Celia featured in FT Critics' Choice by Jackie Wullschlager

September 24 2016Paul works from life only on intensely known motifs, building up and scraping down impasto surfaces whose making mirrors processes of memory and loss. Still,...Read More -

Celia Paul: Desdemona for Hilton by Celia reviewed in The Observer

September 11 2016Pensive and radiating silence, Paul’s self-portraits are also alive with movement. By Laura Cumming. T he painter sits erect for her self-portrait as a solitary...Read More -

Celia Paul interviewed in the Financial Times

September 2 2016Artist Celia Paul explores the beauty of melancholy. By Jackie Wullschlager The British painter talks about women in art and the ‘sadness in my self’....Read More -

Celia Paul interviewed in Bomb Magazine

December 21 2015Celia Paul. By Hilton Als. Women, and their spirits, permeate the work of painter Celia Paul and writer Hilton Als. Paul, for example, has often...Read More