John Kørner: 2006 Problems

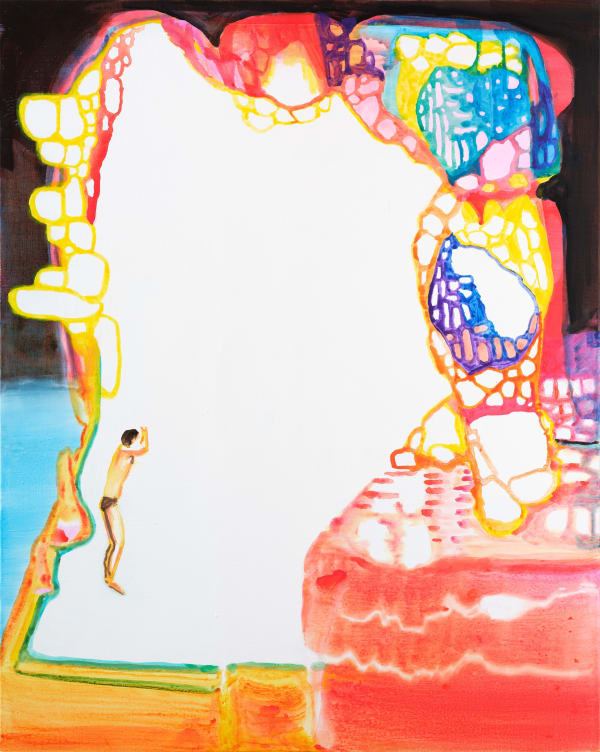

There are plenty of known knowns in what John Kørner has recently painted: ships and trees, men and women, crocodiles and birds, town and country-and most apparently in '2006 Problems', factories and bicycles. These are modern things that we know we know. And as this commandeered logic continues, we know there are some things we do not know (known unknowns), and still others we don't yet know we don't know (unknown unknowns). It's the known unknown phenomena that belong to the realm of Kørner's sustained symptomatology of problems. Visible in paint as coloured blot marks shaped like elongated eggs or dropped-in droppings, problems often line up in Kørner's works as if notes on a musical stave or blobs of clay on wobbly shelves, latent undifferentiated tissue that's waiting to become more specific. Of course how to paint a problem must have been in itself a problem. We may presently be dealing with the problems of this year, or equally, it could be that there is a host of two thousand and six of these quandaries. Kørner makes paintings and painted ceramics, while, as he insists, he is not really a 'proper' painter. His often vast canvases are foremost a way of communicating through a very direct means and are only paintings later, almost by coincidence. All of this is, needless to say, problematic.

There is a spirit of frank lucidity to Kørner's enterprise (where even things that are problematic try their best to be clearly visible) that resists unnecessary obscurantism or any notion that the paintings or the artist somehow have access to privileged information. What do they think? What do you think? What is the chap on the bicycle thinking? What's the problem? In '2006 Problems', problems emanate from the space in between the two workers having a picnic and jamming on their instruments in Music and Problems. Problems are conceits that sprout like errant thought bubbles, or populate buildings, the known and the unknown coexisting. In Conversation a couple discuss their problems while riding a bike; not least, it would seem, the problem of how not to fall off it.

The factory is a big problem. The factories in Kørner's settings are both monstrous behemoths and reassuring, exemplary architectural stalwarts. Employing and providing, and defining leisure-time landscapes via negativa, the factories are necessarily problematic but always unwaveringly modern. They are of course not today's brightly coloured metal boxes of enterprise estates, but upright factories belonging to the town, proudly sporting smoking chimneys like beached ocean liners. Kørner's realm of modern problems is frequented by many such introductions to the badges of civilisation. The schools, the post offices, job centres, museums, hotels and banks which riddle the paintings each occur as indicative services for a developed society. The factory, representing the fundamentals of a manufacturing economy, feeds them all. Akin to the historical fashion in many aspirational European societies for parsing the services, trades and characters of everyday life into painted ceramic tiles-showing the weaver weaving, the miller milling, the baker baking, for example-Kørner's painted scenes reflect on the constitution of societies defined by work, as well as the cultural history of industry, with a supplementary psychology of problems.

Edited extract taken from the catalogue essay 2006 Problems: John Kørner by Max Andrews.

Max Andrews is a writer and curator. He is co-founder of Latitudes, Barcelona.

-

On view at the British Museum – Nordic noir featuring John Kørner and Tal R

September 9 2025On view 9 October 2025–22 March 2026, the exhibition features over 150 works by 100 artists from Edvard Munch to the present day, exploring the macabre, melancholy and sometimes provocative themes that run through aspects of Nordic art.Read More -

John Kørner: Venice Lido Light features in Il Giornale dell’Arte

September 5 2025Riccardo Deni on Kørner's new paintings and sculptures, on view at Victoria Miro Venice from 13 September–25 October 2025.Read More -

John Kørner: Intercontinental Super Fruits at Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit

November 18 2021The exhibition (18 November 2021–30 January 2022) presents work that engages artist Kørner’s visual explorations of the allure of product advertisement and globalization in the...Read More -

John Kørner: Running Box at Riksidrottsmuseet, Sweden

May 20 2019An exhibition (24 May–29 September 2019) of painting, sculpture and installation that takes running as a metaphor for the increasing speed of society. Read more...Read More -

John Kørner: Running Problems at Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens

March 25 2018For his first museum exhibition in Belgium (25 March – 17 June 2018) Kørner creates an integrated environment of painting and installation. A new artist's...Read More -

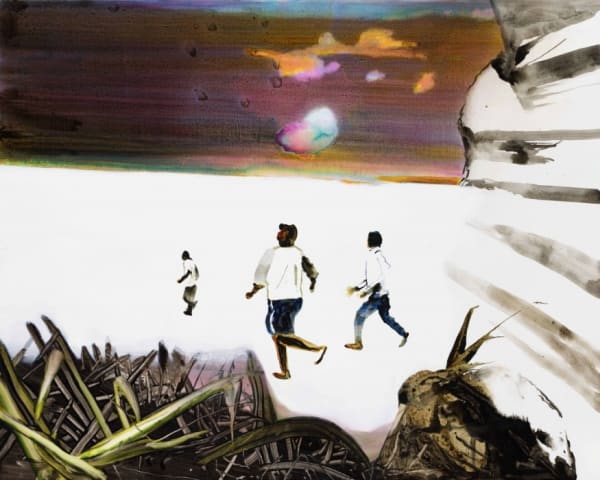

John Kørner: Tripoli – Lampedusa at Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Finland

February 14 2018The exhibition (14 February – 29 July 2018) comprises a site-specific installation of works touching upon subjects ranging from global topics such as migration and...Read More -

John Kørner: Altid Mange Problemer at Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen

June 18 201718 Jun – 13 Aug 2017 In the year of John Kørner’s fiftieth birthday, Kunsthal Charlottenborg will present the largest exhibition ever seen of his...Read More -

John Kørner: Life Attacks You

22 April - 23 October 201622 April - 23 October 2016. John Kørner: Life Attacks You What is the smallest number of brush- strokes needed to tell a story? And...Read More