People she knows and cares about. These are and have always been Celia's subjects. She works from them in silence, demanding stillness from her sitters. And more than just stillness, she requires attention - not to her - but to being there, present. I have sat for Celia many times over the past twenty years, and know how exigently she requires one's conscious presence. She detects any glazing over of my eyes, any failure of being there present in the studio. Yet though fully conscious of where I am and what I am doing, my eyes are hardly ever focused upon the studio or Celia herself, who is in my field of vision. I am not looking at what is around me, indeed though my eyes are open I am not looking at all. One is gazed at intensely without returning the regard, but always in some way aware of the gaze. There is a close connection between this scenario and the paintings Celia creates. The qualities of stillness and intensity characterise them along with the strange intimacy of an interaction when nothing is said and no glances are interchanged.

Whatever their immediate qualities - and they are beautiful, pleasing to look at, often striking - what they are on a deeper level appears only if one gives them time. They repay a longer gaze, a concentration of attention, and they become themselves, as one looks. There is an interaction between the viewer and the work and a dynamic which takes time, a process, through which the work comes to be what it is, and to give itself to the gaze. It is as if the intensity and stillness integral to the creation of the work, which may have taken up many weeks and many sessions, is required in responding to the works, which then at last give back something akin to the real presence of the subject. This presence is not a matter of photographic fidelity, of likeness in any literal sense of the word. What comes into being under the viewer's gaze is the presence of a person in some particular state or mode of being, one which cannot be expressed in a word, indeed, one which the viewer takes in without being able to say what it is.

There is an interaction between the viewer and the work and a dynamic which takes time, a process, through which the work comes to be what it is, and to give itself to the gaze.

I can suggest it is connected intimately with and somehow reflects the process of creation. But it is more difficult to say what it is about the painted surface that enables this processual coming to be of the subject. Perhaps it is closely connected with the way in which the subject inhabits the space. The painting often contains nothing to suggest an actual physical environment – a place, or the studio in which the sitter was placed. And yet in the viewer’s process of engaging with the work its subject comes to inhabit a physical space. As one looks one experiences this coming to be in a space, and this is intimately bound up with the sense of the presence of the subject. For somehow the figure generates the space it inhabits, a space that is not anywhere else, is not anywhere except where the subject is. How this comes about is difficult to say. Is it a matter of the positioning of the painted figure within the space of the canvas? Sometimes it seems to be a matter also of the poise of the head on the neck. Sometimes, too, of an interplay between the hands and the head as two distinct foci of attention and of the play of the gaze between one and the other in a dynamic which resolves itself in the realisation of the subject’s presence in a physical space.

In the case of the watercolours a painted figure is set in a blank white expanse of the paper on which it is painted, while in the oil paintings the figure is set amongst shades and swirls of paint which do not depict anything but which enable the process of the coming to be of the physical space inhabited by the subject. Sometimes there is more; the chair on which the subject sits, a skirting board behind the chair generating a sense of a wall behind the sitter. Then the location becomes more specific, a place, but minimally so. There is still something uncertain yet particular to the subject about that depicted space.

People she knows and cares about. Also places. Celia paints what she sees from the flat where she has lived and worked for more than thirty years. To the north the British Museum, the Post Office Tower and the plane tree in Great Russell Street. To the south she looks out upon the extraordinary tower of Hawksmoor’s St George’s Bloomsbury. The show includes two paintings of the landscape and sea around Lee Abbey, her home during her adolescence. Once, notably, she travelled to India, to Trivandrum, to paint the house where she was born and lived in her early childhood. Though not represented in this catalogue, the show includes two paintings of the interior of her flat, of the room where she lives and sleeps. These are the physical environments of her life. While these places remain recognisable in her paintings they are transformed so as to become autobiographical. They are bearers of her feelings, projections that seem to carry more complex but mysterious messages.

While these places remain recognisable in her paintings they are transformed so as to become autobiographical. They are bearers of her feelings, projections that seem to carry more complex but mysterious messages.

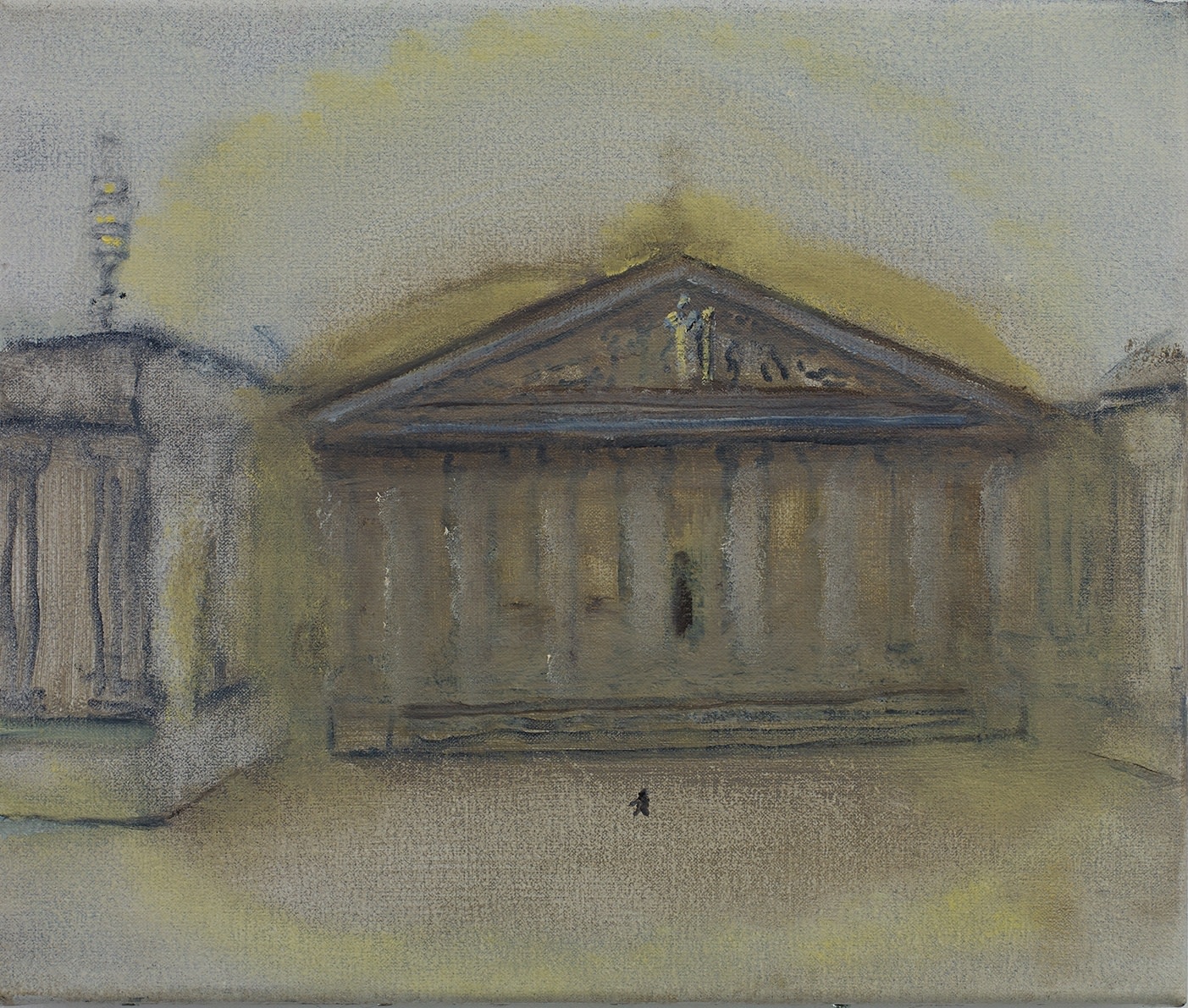

Thus in two of the paintings in the current show, the British Museum, which she has often painted in this way, becomes a louring, dark presence. There is something frightening and death-like about these images. The figure in the centre of the pediment (a version of the central figure in Westmacott’s complex and optimistic many-figured sculpture, The Progress of Civilisation) has become an enigmatic fearful figure: the angel of death? a judgmental servant of the divine? And directly below it in the space of the courtyard is a tiny figure of a human being making her way towards the black destination in front of her. In one of the two paintings the bleakness of this story is ambiguously mitigated by the branches of the plane tree, which cut across the foreground with slivers of light. The third painting of the museum is lighter and includes the two wings flanking the pillared portico. They seem to be inviting the tiny labouring figure towards the steps and the black hole of the entrance behind the pillars.

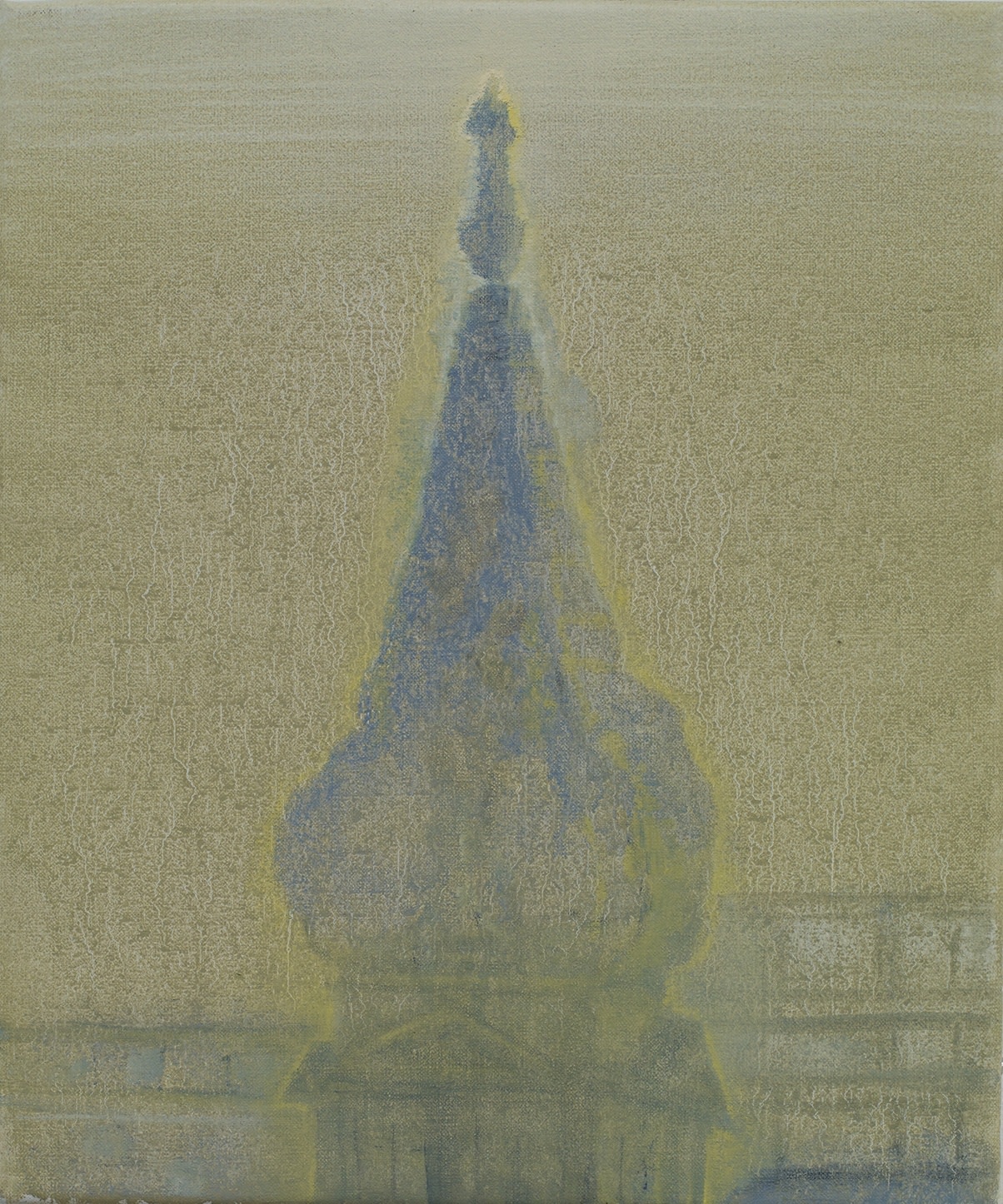

The Post Office Tower presents a complete contrast to the mood of the dark paintings of the British Museum. It is a soaring golden affirmation, rising alone and splendidly out of the earth without any suggestion of a city around it. Saint George’s Bloomsbury appears in two paintings and the feeling in both is dreamy and optimistic. In one, St George’s by Moonlight, the giant figure of George I, which surmounts the spire, looks towards and is illuminated by the moon, while beyond, the city lies, a rag-tag of buildings under the night sky, answering the jumble of roofs and chimneys out of the which the spire rises. The second shows the spire on its own on a misty morning when the edges and detail have all been softened. There is a poetic wistful feel to this painting.

The Post Office Tower presents a complete contrast to the mood of the dark paintings of the British Museum. It is a soaring golden affirmation, rising alone and splendidly out of the earth without any suggestion of a city around it.

The difference between the ways in which Celia represents places and people is marked. In the case of people she gives herself up to them, and, though the representation is an expression of her vision and her feeling, what she brings to life respects the otherness of the subject. In the case of places she allows her feeling and what the places mean to her to determine their representation, so that as I have said they become autobiographical.

Different again is Celia’s treatment of herself in her selfportraits – there are seven in this show. For in the process of their creation there is no sitter, only the estranging familiarity of her own image objectified in a mirror. And this is reflected in the works. They are immediately powerful. They command attention. Quite unlike her paintings of other people, her self-portraits do not give themselves to the viewer’s gaze. They impose themselves upon it. The sense of herself that these pictures communicate is not a kindly one.

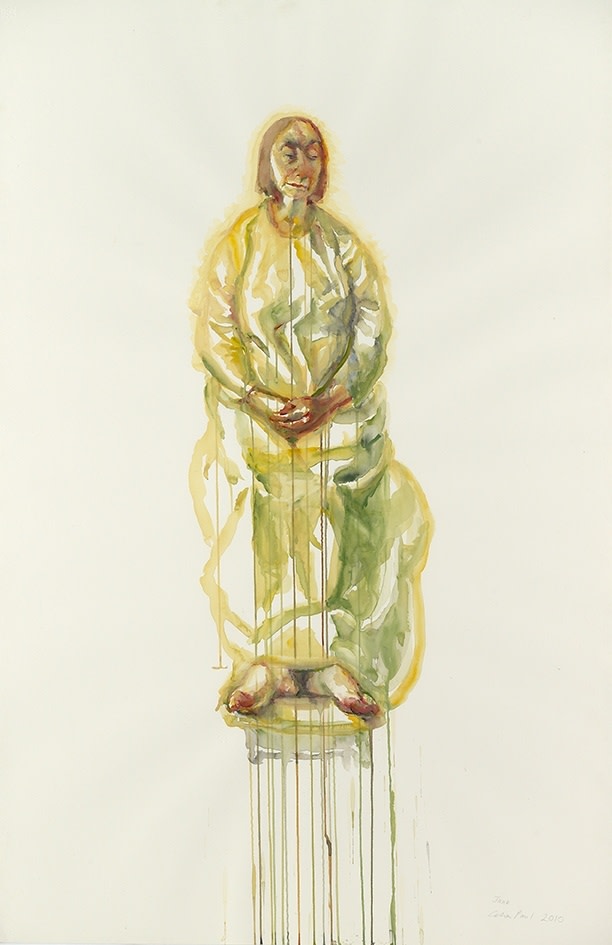

In the five small oils painted in successive months between May and November 2013 Celia presents herself bleakly, unforgivingly. There is something eerie and frightening about the self she depicts in the August painting. One feels Celia does not love herself. The most sympathetic of her self-portraits is the full-length oil, Self-Portrait in a Narrow Mirror. Even here, though the subject seems at peace, there is remoteness, an almost Buddha-like sense of isolation and self-containedness about it. It is striking that compared with her paintings of other people these paintings lack empathy. Yet they share a sadness, a sadness akin to the sadness of clowns. For Celia paints herself with touches of savage humour, achieved through slight exaggerations, so that the paintings defy sympathy.

Yet they are integral to her work, for, of course, she is at the very centre of the people and places close to her. For what she paints is her life.

This essay was first published to accompany the 2014 Victoria Miro exhibition Celia Paul, Paul's first solo exhibition at the gallery. The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with essay by Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Hilton Als.

About Celia Paul

Celia Paul’s art stems from a deep connection with subject matter and is quiet, contemplative and ultimately moving in its profound attention to detail and deeply-felt spirituality. She is renowned for her intimate depictions of people and places she knows well. Recent solo exhibitions include Celia Paul, curated by Hilton Als, which originated at the Yale Centre for British Art in 2018 and subsequently toured to The Huntington; and Desdemona for Celia by Hilton, at the Gallery Met, New York (2015–16).

Paul’s paintings were also included in All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life at Tate Britain, 2018. Last year, the artist published her memoir Self Portrait, praised by notable critics, including Zadie Smith in the New York Review of Books. Paul has just finished working with filmmaker Jake Auberbach on a documentary about her life.

About Steven Kupfer

Steven Kupfer is a writer, philosopher and poet and Celia Paul's husband.

Images from top:

Figure Approaching the British Museum, 2013

Steve, 2019

Kate in White, 2014

Jane, 2010

Annela 3, 2013

Room, 2013

British Museum and Plane Tree, February 2013

St George’s Bloomsbury, Early Morning, 2013

Post-Office Tower, 2013

Self-Portrait, August, 2013

Self-Portrait in a Narrow Mirror, 2013-2014

Steve, 2017

All works © Celia Paul

Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Portrait of Celia Paul © Antonio Olmos