1 . A Short Biography of Wangechi Mutu

2. 1971. Idi Amin takes over Uganda. Wangechi’s father buys a Peugeot 504. He and her uncle love to smoke Rex Cigarettes. All Kenyan beer bottles are stumpy and green. Over beer they discuss where they were when Jim Reeves died in a plane crash.

3. You are Wangechi Mutu. Born in Kenya.

4. You are Wangechi. Born. 1972. Born with a strange, bewildering left eyebrow. In a hospital run by Catholic order called Saint Discipline of The Blood. They are nice to babies.

5. 1972. All Kenyan beer bottles were green. Franklin Boukaka’s song, Aye Afrika, (Le Boucheron) will play every night late in shortwave all over East Africa, a sad, sweet feeling. Inside our bloodstream of feeling independent.

6. You are a supermodel Kenya nomad four-year-old cowherd Afro-girl with tulle claws and steel killing teeth.

7. And you know that you have not been cow-herding. You just dreamt you were.

8. That it is not day. It is night. That your eyes are sticky. That you are sick. You know that kiss, your mother’s fever kiss? It comes to you every year. She sings softly and spits her chew into your mouth, herbs and hot mush, pastes of beans, blood and milk, in small bits. Then your mum croons and goes out to stick her beak in the belly of a motorcycle trapped in a fashion shoot. Even now you can smell burning meat. Your fingers dream-bling!

No, Wangechi, inside your head a thousand hairy caterpillars are grazing and chewing mildly, stinging and tingling.

9. No, Wangechi, inside your head a thousand hairy caterpillars are grazing and chewing mildly, stinging and tingling. Your mother’s arms are soft, but hurt.

10. You are Wangechi. With Human Bovine petechial fever (Ondiri disease). Cattle diagnosed only in Kenya. Symptoms: widespread petechial ecchymotic haemorrhages on the mucosal surfaces, and throughout the serosal and subserosal surfaces of body organs, cavities. Fatal in up to 50% of untreated cases. Transmitted by an arthropod vector, yet to be identified.

11. You are Wangechi. Your fever-dream is crumpling in fits and starts, the clarity shifts, and you are pulling an udder, biting it hard, it breaks, blood and milk spill over you and you drink and your head is a soft pumice stone.

12. This is a story taught the first few weeks of Kenyan primary school. Wangu wa Makeri, a woman and Gikuyu chief. Her dictatorship of women is toppled when the men decide to get the women of the village pregnant.

13. You woke up days later. Fine after eating Apro-junior. Which is fuzzy sweet.

14. For the first six months of her life Wangechi lived with a dramatically mobile left eyebrow. Every time her mum took her to the doctor the feral eyebrow was calm. It seemed to move unhindered up and down her forehead, left and right of her forehead, and then return to position whenever the emotional viewer sought a witness. One night her father saw it sitting right above her right eyebrow. He screamed.

15. This magical effect never lasted long enough to be medically diagnosed. Their home village, once named Kwa Wangu wa Makeri, was agitated to near violence by the idea of this eyebrow. They soon forgot for they were riveted by Little House on the Prairie on television.

16. Ayee Afrika, ohh Africa, Ohh Liberte. Le Boucheron.

17. In the early seventies, Franklin Boukaka began to transfer his moral outrage from song to action. He joined a group of disaffected Congolese with socialist leanings in a plot to overthrow the government of Congo-Brazzaville. The attempted revolt of February 22, 1972 ended in failure. Although Boukaka’s name appeared on lists of arrested participants, his death was announced a few days later. Many Congolese suspected he had been summarily executed. In his brief but active career, Boukaka grew from teenaged pop singer to principled social critic. Combining lovely melodies with trenchant lyrics, he critiqued his people’s changing lifestyles and goaded the ruling elite in a manner similar to that of Bob Marley and Fela Kuti. (Gary Stewart, Rumba on the River, Verso, London, 2011.)

1970s. Kenya is in every fashion magazine, every animal print magazine. It is a big Safari Animal park fashion shoot.

18. She is Wangechi. The first few days her parents considered calling her Susan. Anne. Ruth. An Aunt from Nyeri strongly suggested the name Purity Scholastica to sit next to Wangechi on the birth certificate. A family friend was sure Jackie Onassis Mutu would have worked much better.

19. Wangechi Mutu.

20. Mutu. Mud. Utu. Muntu. Person. Human.

21. Ubuntu In Nguni. Ubuntu means Personhood. Utu in Kiswahili means Personhood.

22. Bantu. Is. A. Language Group.

23. Anthropo-logical.

24. uBuntu Linux operating system free software named after the Southern African philosophy of ubuntu (literally, “human-ness”), which often is translated as “humanity towards others” or “the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubuntu_(operating_system)

25. Your name is Wangechi. You are six years old. It is blurry and feels late, and you are sure you have herded the whole day and sit under a tree in the last heat of dry near Lake Naivasha. You know you are wrong. Cows mumble and groan with gas and grass in their bellies. An Anthro-Geographic Lion looms. You scratch your vagina idly and think of your claws tearing his belly.

26. You are Wangechi. Soon, evening is coming, the first small coolings are present, the cattle are still, your friend’s play-fights have become murmurs and warm whispers, flesh-slapping games and giggles. You blink one eye open, and the softening sun burns your sight neon-blind. From your eye-shut shiny black tunnel you are carrying tumbling limbs on night-raid runs, and now, in transition, you see a thousand twisted acacia-men walking toward you, the fading sun

behind them.

27. She is D.I.S.C.O! She is D.I.S.C.O!

28. You Are Wangechi. You can see their desire, it is star-bursts of heart stopping thrill-power in your sunblown pupils, coils and patterns of neon greens, reds, yellows, sun-shaped and pupil-shaped explosions of distorted light. You shut your eyes fast, in that moment your eyelids are a sky of shining bloodcoloured flesh, with a fine glowing network of branches: of fear and coming death or glory.

29. A bull back jerks upwards in your ears, and coughs out a deep painful moo, a long painful jet of hot piss on the ground, and the cows are excited and gather together.

30. She is D, Delirious. She is I, Irresistible. She is S, Super Sexy. She is C, Such a Cutie. She is O-O ooo.

31. They would have considered, the New Christians, cutting your clitoris for Anti-Colonial reasons in the 1920s.

32. She is D.I.S.C.O!

33. They go to Mission School Not Knowing what they are releasing in their grandchild.

34. But knowing it is a kind of release.

35. 1970s. Kenya is in every fashion magazine, every animal print magazine. It is a big Safari Animal park fashion shoot. On Kenya Television too.

36. Power in a new world.

You can see their desire, it is star-bursts of heart stopping thrill-power in your sunblown pupils, coils and patterns of neon greens, reds, yellows…

37. Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual or organization’s lifetime, and are kept to show the function of that person or organization. They have been metaphorically defined as “the secretions of an organism.” Wikipedia.

38. Kenya is where old Fashional Geographic magazines come to die. And Vogue. Playboy. Right On. Ebony. GQ.

39. There was a short frenzied season of drawing lollipops on walls.

40. You are Wangechi. One racing-car ostrich crouches near, and you look at him, and he is carrying his fluffy bleeding entrails, clouds above are full of open nerve endings and painfully pink biolight.

41. Zebra-coloured tourist vans are part of Kenya’s national archive of images.

42. Your mum’s New Imported magazines Smell Good.

43. You are Wangechi. You are swimming through the dreaming hot porridge in your head when they come for you. Your grandmother’s screams are stranded in between three soft hot thuds.

44. Cowherd! Your ears rule every feeling. They silence the soft pad of flesh just below your kneebones which are cutting in the stones and dried sticks. Goat-legs are backwards.

45. Cow-herd! You can hear your kneebones scream, and you move more efficiently through the cooling breeze, your body becomes wind, and in the ripe attacking dirt, your heart glows because you will be the first to feel your hands grope at your nearest sleeping friend’s body. She snorts, you cover her mouth, put your mouth at her ear, and say the secret word.

46. Girls go hunting dressed in vinyl, for fur.

47. She starts awake. Her warm body and heartbeat follows the shape of your movements, as the next shape wakes, and the next, and guns are collected, and you shall attack first. Your personal glory, chest-glowing like a crown of vinyl sunthorns stinging in your ears and neck as you arrive home at sunset with a crowd of cattle and your troops cheering behind you.

48. “The chief difficulty Alice found at first was in managing her flamingo: she succeeded in getting its body tucked away, comfortably enough, under her arm, with its legs hanging down, but generally, just as she had got its neck nicely straightened out, and was going to give the hedgehog a blow with its head, it WOULD twist itself round and look up in her face, with such a puzzled expression that she could not help bursting out laughing: and when she had got its head down, and was going to begin again, it was very provoking to find that the hedgehog had unrolled itself, and was in the act of crawling away: besides all this, there was generally a ridge or furrow in the way wherever she wanted to send the hedgehog to, and, as the doubled-up soldiers were always getting up and walking off to other parts of the ground, Alice soon came to the conclusion that it was a very difficult game indeed.” (Alice in Wonderland)

49. The tractor spareparts make really nice earrings. Wangechi wonders why butterfly wings leave powder on the fingers.

50. “The Kikuyu were Matriarchal – power in the hands of women – before men finally overthrew them.”

51. 1978. In a glorious three days of measles, Tree-Top Orange Squash, Ribena and House of Manji biscuits, Wangechi read Alice in Wonderland.

52. Rich ripe jewels, like screaming ovaries, and crushed iridescent insects in the sand on your verandah. She has a famished African Baby, like Madonna.

53. Barbie dolls are imported at great expense for a world starved Moi Kenya.

54. “I know not to go too far and over-complete it because at that point it’s quivering and almost has a vibration.” (Wangechi Mutu)

55. We watched, in the 80s, with only one television station, one radio station, as teenagers…

56. Michael Jackson’s face melt slowly.

57. There was so little to watch. We had to wait months for the next development.

58. Kama Kama Kama Kama Kameleon, you come and go, you come and go-o –oh-oh.

59. President Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi banned toy guns and other foreign inFluenzas.

60. Wangechi goes to The Carnivore for the first time in a friend’s stolen car wearing shoulder pads and bopping to Milli Vanilli. Early morning, sun is up, they crawl out scared and full of alcohol and Wangechi notices a crushed chameleon next to the ladies toilet. She leans to pick it up and thinks about cannibal butterflies, and giggles. It is leathery like silk. Driving past the Military hospital on Mbagathi Road, where, every few months, drunk teenagers in their parents’ borrowed cars, crashed, died, or were dismembered. They kissed. “Nyeri chics are really brown,” he said, “and when they grow up they beat their husbands.”

Girl! Behind your crawling back, the lowering sun is heating up, not above the head where it is just everybody’s. It is yours now. It burns the skin of your neck.

61. Girl! Behind your crawling back, the lowering sun is heating up, not above the head where it is just everybody’s. It is yours now. It burns the skin of your neck. In the distant world outside this tunnel, the cattle have gathered together waiting to go back to the boma and they shuffle restless, complaining in your earlobes as you creep forward, in your private tunnel, with your private last sun.

62. A hot golden sunset magma of humiliation surges up your teenage throat, and you let it gurgle, not into tears or rage. No. You are Wangechi. Cowherd Supermodel. You push it down back to the top of your stomach, and stretch your mobile loose mouth to its limits. Whenever you do this, you find that a crowd bubble of gentle laughter makes you the centre of friends. But they are hostile now with your weakness in front of them.

63. Iman was discovered herding goats in Somaliland riding a zebra. We like her coz she left Kenya.

64. We waited in the 80s, for friends to come from America with pirated tapes of the latest music. Or Top of the Pops from England which we tuned into carefully on short wave radio, with crackles, bells and whistles.

65. Kenya is flat. Moi season is tired. No money. No Dreams. No Hope. In Kenya. Get a Visa and Run if you can. Anywhere. Or Drink. Or Become a Born Again Christian.

66. Eddie Murphy is Coming to America.

67. They all follow you to Americanah.

68. Wangechi Mutu is going to America to study Fashion Merchandising for Safari-chic Cyborgettes with longish goat-legs and crippled bleeding gold boots.

69. Like This:

70. uterine catarrh by Wangechi Mutu: This yellowing paper is an important piece of medical history. This young man has a third eye – a wisdom to offer? A possible insight? He too is a recipient (knowing or unknowing) of this knowledge – if only from a straight-laced high school lecture about syphilis. Ricord is an early, and substantial, original source about gynecological disorders. Part of our casual knowledge about this has filtered down from him. Our young man has magazine lips too: cutout pink lipstick lips, large and lush: the sort of lips some pay for collagen to get. How lucky, Wangechi seems to suggest somewhat wickedly? That lips are the one territory we have that are wanted by the magazine perceptions of How You Must Look. A bit of the lip is red, lipstick again. The lips are pasted on, and slightly out of place – and it starts to arrive that what seems grotesque here is not.

71. The young man is in good health – and the shapes imposed upon him leave his face with integrity. The questions being asked here seem to be about membership: this black man is, too, an heir of medical and other histories that have come before him – but his choice and participation will be original – his colour, and its history, will bring their own contexts and insights. His third eye. His membership of this world has its inflammations; but has also wisdom. His third eye – digging deep into his brain, has received yellowed ideas, will provide eurekas and will give birth to things. It is not for nothing that his brain is a womb.

72. “Wangechi came to the States in 1992 to study at Parson’s, but transferred to Cooper Union, where she received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1996. She then went on to pursue her Master of Fine Arts degree in sculpture from Yale University School of Art in 2000. After receiving her MFA, Wangechi did not return to Kenya until 2012.”

73. Your private day-dreams have stolen you from them. Your smile makes other people smile. Now, they jeer at you, and when the now soft blue bubbles of laughter magma surge up and turn the red sunset gold, your limbs leap up with them, and you throw yourself into the herd of friends, elbows and crowd-noise, and race forward, faster than all of them, limbs freer, cows chasing behind.

How lucky, Wangechi seems to suggest somewhat wickedly? That lips are the one territory we have that are wanted by the magazine perceptions of How You Must Look.

74. Wangechi was unable to return home for seventeen years. A simple mistake left her battling to legalise her stay in America.

75. “It was like a long sentence... (pun intended)” Wangechi Mutu.

76. You make And You. Do.

77. Exile.

78. Below (79-104) is an excerpt from Yvonne Owuor’s short story Weight of Whispers:

79. What is my name? I frown. What is my name?

80. I was once drinking a good espresso in a café in Breda, in the Netherlands with three European business contacts. Gem dealers. We were sipping coffee at the end of a well-concluded deal. A squat African man wearing spectacles danced into the café. He wore a black suit, around his neck a grey scarf, in his hand a colorful and large bag, like a carpet bag. Outside it was cold. So easy to recall the feeling of well being a hot espresso evokes in a small café where the light is muted and the music a gentle jazz and there is a knowing that outside it is cold and grey and windy.

81. The squat African man grinned like an ingratiating hound, twisting and distorting his face, raising his lips and from his throat a thin high sound would emerge:

82. “Heee heee heee, heh heh heh.”

83. Most of the café turned back to their coffees and conversations. One man in a group of three put out his foot. The squat African man stumbled, grabbed his back to him. Rearranged himself and said to the man:

84. “Heee heee heee, heh heh heh.” […]

85. Sweat trickled down my spine. I think it was the heat in the café.

86. “What is your country of origin?” I ask him. Actually, I snarl the question at him and I am surprised by the rage in my voice. He mumbles, his face staring at the floor. He lowers his bag, unzips it and pulls out ladies intimate apparel designed and colored in the manner of various African animals. Zebra, leopard, giraffe and colobus. There is a crocodile skin belt designed for the pleasure of particular sadomasochists. At the bottom of the bag a stack of posters and sealed magazines. Nature magazines? I think I see a mountain on one. I put out my free hand for one. It is not a mountain, it is an impressive arrangement of an equally impressive array of Black male genitalia. I let the magazine slide from my hand and he stoops to pick it up, wiping it against the sleeve of his black coat.

87. “Where are you from?” I ask in Dutch.

88. “Rotterdam.”

89. “No, man...your origin?”

90. “Sierra Leone.”

91. “Have you no shame?”

92. His head jerks up, his mouth opens and closes, his eyes meet mine for the first time. His eyes are wet. It is grating that a man should cry.

93. “Broda.” he savors the word. “Broda... its fine to see de eyes of anoda man...it is fine to see de eyes.”

94. Though his Dutch is crude, he read sociology in Leeds and mastered it. He is quick to tell me this. He has six children. His wife, Gemma is a beautiful woman. On a good day he makes 200 guilders, it is enough to supplement the Dutch state income and it helps sustain the illusions of good living for remnants of his family back home. He refuses to be a janitor, he tells me. To wear a uniform to clean a Europea toilet? No way. This is why he is running his own enterprise.

95. “I be a Business Mon.”

96. “Have you no shame?”

97. “Wha do ma childs go?”

98. “You have a master’s degree from a good University. Use it!”

99. Business man picks up his bags. He is laughing, so deeply, so low, a different voice. He laughs until he cries. He wipes his eyes.

100. “Oh mah broda...tank you for de laughing...tank you...you know... Africans we be overeducated fools. Dem papers are for to wipe our bottom. No one sees your knowing when you has no feets to stand in.”

101. He laughs again, patting his bag, smiling in reminiscence.

102. “My broda for real him also in Italy. Bone doctor. Specialist. Best in class. Wha he do now? Him bring Nigeria woman for de prostitute.”

103. Business man chortles.

104. “Maybe he fix de bone when dem break.” I gave him 20 guilders.

105. End of excerpt from Yvonne Owuor’s Weight of Whispers.

The Nguva, accompanied by pythons in vinyl land, feral in a weave, and starving after sinking and bursting over the Atlantic… swims across the lagoon…

106. Your archives do not leave you. But you like remixing. See 1-105 above.

107. Hindsight. Hind-Quarters. Thighs.

108. Your work makes new things, and remixes.

109. Her work became a middle-passage, never real in America, never real at home.

110. She built a world to live in that Africans can inhabit.

111. An African global citizen is the inheritor of all archives.

112. In the season of Afro-futures.

113. Once distressed, distorted, re-made, this global citizen releases us from ugga booga fears of the hegemony that makes these magazines, and freezes

114. Just consume, brown world, just eat what we throw at you. Beg, African, Beg for AID.

115. The hegemony fills all our senses with its spectacle. And then you realize that you can remix in exile.

116. Remix: religious ritual that removes demons.

117. “Pleased to present a solo exhibition of new work by Wangechi Mutu titled Nitarudi Ninarudi, Kiswahili for I plan to return I am returning. Nitarudi Ninarudi. The tone of the work has shifted towards a deeper exploration and disclosure of the artist’s own experience in the Diaspora. Ideas around longing, memory, and exile resonate and subvert traditional notions of a singular place of origin. Fusing her Kenyan experience with inflections of other cultural influences, the work calls into question any notion of a static identity and firmly rejects the centralization and dominance of Eurocentric constructs within and outside of her homeland. Nitarudi Ninarudi expresses the complexity of longing for a place that is alive in the memory in a very different way than in the physical reality – a place as evasive and fleeting as the identities one negotiates when they are relocated, bringing into play issues of transformation, translation, and even personal survival.”

118. We forgot to mention the armless, loving, legless, floating, gorgeous foetal season before the baby.

119. Remix: Only a small bodypart now in the making of something utterly new.

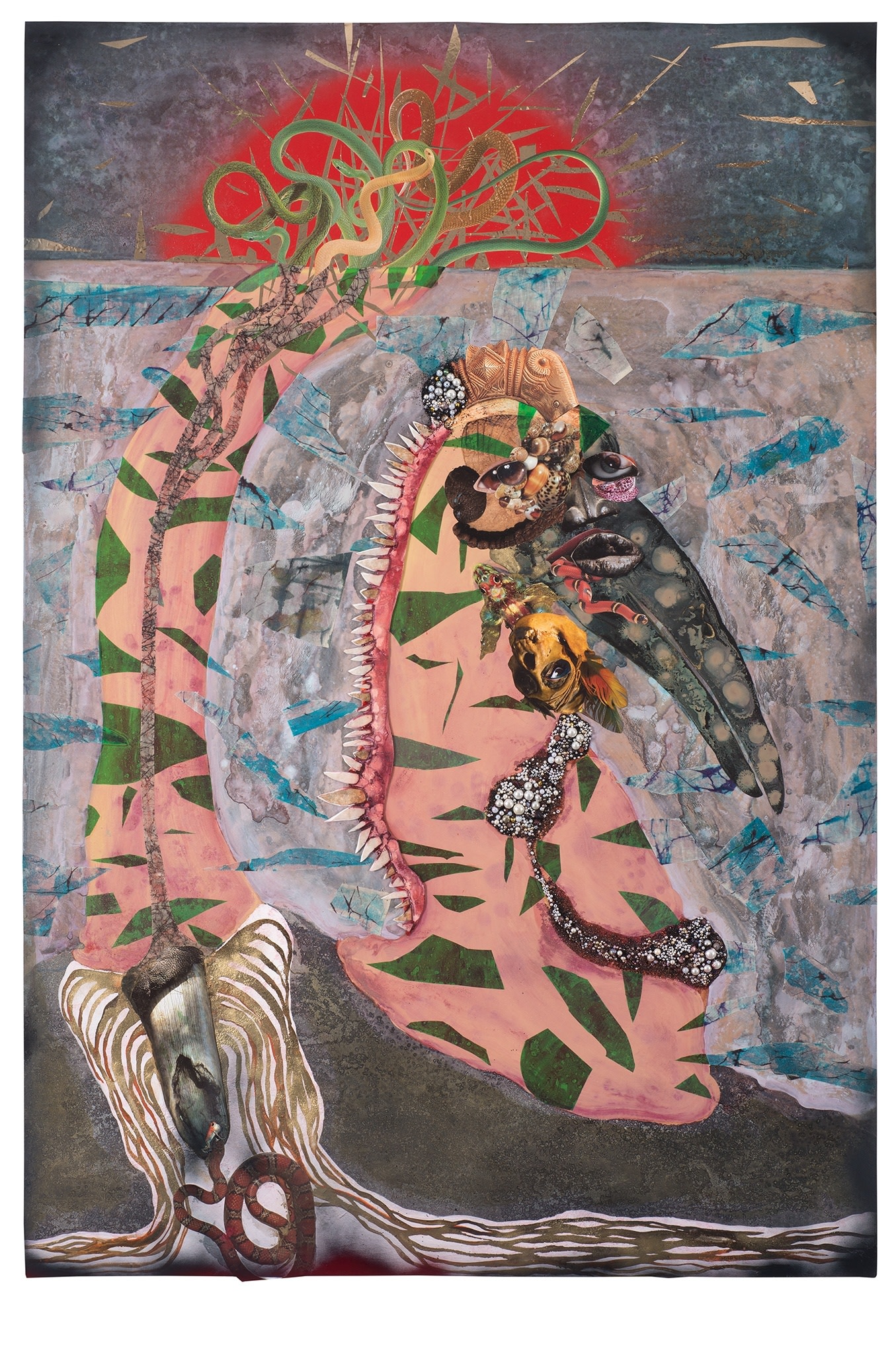

120. The house is too full of stuff. Rivers and Banks are Bursting. Everywhere.

121. “Wangechi Mutu’s interest in the subtle distinction between Nitarudi and Ninarudi is embedded in the ever-so-slight difference between the desire and promise to return, versus the absolute insistence and the capability to come back to a place.”

122. I plan to return I am returning

123. The Goodyear Blimp decides to fly back to Kenya slowly swelling up in studio over the last twenty years, the whole world digested by capital and your archive, or remaking. She can leave America legally now. We are carrying fake hair, magazine parts, machinery, cut-outs, Beads, Porn Kings, viable monster babes who hunt, jewels, gynecological drawings, Brooklyn, blood, flowers, petals, blood, knives are high heels, we carry worlds of dead mushrooms.

124. The Blimp blings with Santigold, it flies out of Wangechi’s studio window, burping birds, it recrosses the Atlantic on video Eating Everything.

125. In The End of Eating Everything, a new body must be found, that one burst and fell to the sea.

126. The Nguva, accompanied by pythons in vinyl land, feral in a weave, and starving after sinking and bursting over the Atlantic, meets Mami Wata posters as she walks through West Africa and Congo and swims across the lagoon in Mpeketoni, to Lamu where Nguva looks to eat again.

127. The flat wall hangings, swollen into giant helium video.

128. And Nguva is Wangechi in grit, flesh and blood performing.

129. Back for a season of home-making. It’s hard for a mermaid to find her feet. There is work to do.

130. She is starving.

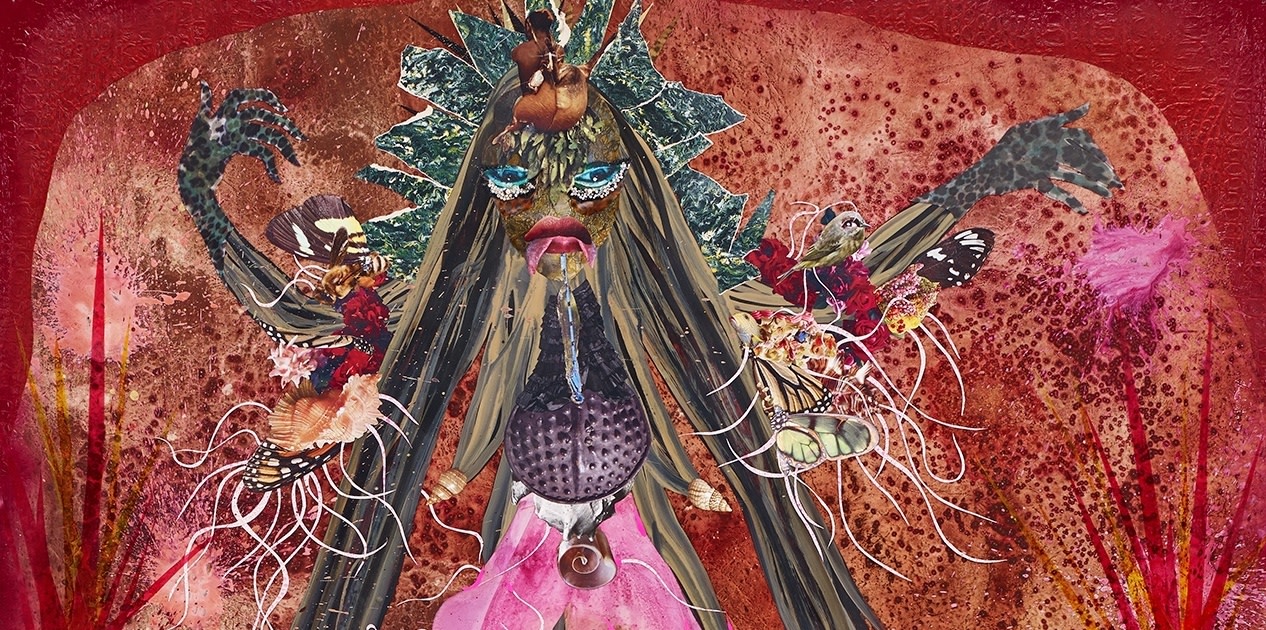

This text was originally published to accompany Wangechi Mutu's exhibition Nguva na Nyoka. Held at the gallery in 2014, Nguva na Nyoka (meaning 'Sirens and Serpents' in Kiswahili) debuted a body of collage, video and sculptural works drawing on such diverse references as East African coastal mythologies (particularly of nguvas, or water women), gender and racial politics, Western popular culture, Eastern and ancient beliefs and autobiography.

It appears in the accompanying hardback book, along with a text by Adrienne Edwards and illustrations of works in the exhibition.

About Binyavanga Wainaina

Binyavanga Wainaina (1971–2019) was a Kenyan author, publisher, journalist, commentator and activist who made a revolutionary impact on literature from and about the African continent. He won the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2002 and went on to establish Kwani?, a literary magazine that offered a platform for new Kenyan writers. His debut book, a memoir entitled One Day I Will Write About This Place, was published in 2011. In 2014 he was named one of Time magazine’s '100 most influential people'

About Wangechi Mutu

In collages, films, sculptures and installations Wangechi Mutu reflects on sexuality, femininity, ecology, politics, the rhythms and chaos of the world and our often damaging or futile efforts to control it. First recognised for paintings and collages concerned with the myriad forms of violence and misrepresentation visited upon women, especially black women, in the contemporary world, Mutu’s work has often featured writhing female forms. More recently, exploring and subverting cultural preconceptions of the female body and the feminine, in her works Mutu proposes worlds within worlds, populated by powerful hybridised female figures. Significant recent exhibitions include the Whitney Biennial 2019. The artist has created sculptures for The Met's Fifth Avenue façade niches – the first-ever such installation on the Museum's historic exterior – inaugurating a new annual artist commission series.

Images from top:

Portrait of Wangechi Mutu, © Kathryn Parker Almanas, 2014

My Mothership, 2014

Even, 2014

History Trolling, 2014

Killing you softly, 2014

Killing you softly (detail), 2014

Beneath lies the Power, 2014

All you Sea, came from me, 2014

All you Sea, came from me (detail), 2014

The screamer island dreamer, 2014

Nguva (still), 2013

Installation view, Wangechi Mutu: Nguva na Nyoka, Victoria Miro, 14 October–19 December 2014

Sleeping Serpent (detail), 2014

A Tail about Sunset, 2014

Wangechi Mutu, Binyavanga Wainaina and Grace Jones at the opening of Wangechi Mutu's exhibition Nguva na Nyoka, Victoria Miro, October 2014, photo courtesy Wangechi Mutu

Wangechi Mutu and Binyavanga Wainaina, photo courtesy Wangechi Mutu

All works © Wangechi Mutu, courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro

Extract from Weight of Whispers by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor (referenced within Binyavanga Wainaina’s essay) © Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, used by permission of The Wylie Agency (UK) Limited

Extracts referenced within Binyavanga Wainaina’s essay from the press release for the exhibition Nitarudi Ninarudi at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, 2012