Njideka Akunyili, Jules de Balincourt, Ali Banisadr, Hernan Bas, Joe Bradley, Cecily Brown, Peter Doig, Inka Essenhigh, Eric Fischl, Barnaby Furnas, David Harrison, Secundino Hernández, Nicholas Hlobo, Chantal Joffe, Sandro Kopp, Harmony Korine, Yayoi Kusama, Glenn Ligon, Wangechi Mutu, Alice Neel, Chris Ofili, Celia Paul, Philip Pearlstein, Elaine Reichek, Luc Tuymans, Adriana Varejão, Suling Wang, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

An exhibition in support of the Bottletop Foundation.

Since the infancy of cinema, when moviegoers would watch in disbelief as two-dimensional images leapt into life, painting and film have enjoyed a fruitful if sometimes fraught relationship. Cinematic Visions: Painting at the Edge of Reality takes as its starting point an ongoing dialogue between the two media, looking at the enduring influence of film on visual artists and how in an age of the Internet and social media painters continue to engage with and redefine their practice in relation to the moving image. At the exhibition's heart are questions about time, technology, narrative, memory and their impact upon contemporary painting.

Selected Images

-

![]()

Ali Banisadr, HRH, 2013

-

![]()

Hernan Bas, HOAX REVEALED: the Devil of Deckheart Manor caught on film, 2013

-

![]()

Jules de Balincourt, Hidden men and lost monkeys, 2013

-

![]()

Peter Doig, Two Students, 2008

-

![]()

Peter Doig, Trinidad & Tobago Film Festival Poster, 2008

-

![]()

Inka Essenigh, Daphne and Apollo, 2013

-

![]()

Barnaby Furnas, Creation of Adam, 2013

-

![]()

David Harrison, Midnight Meet, 2011

-

![]()

David Harrison, Moonstruck, 2011

-

![]()

Sandrop Kopp, Ambassador, 2013

-

![]()

Yayoi Kusama, IN THE SPRING SUN, 2009

-

![]()

Chris Ofili, Ovid-Windfall, 2011-12

-

![]()

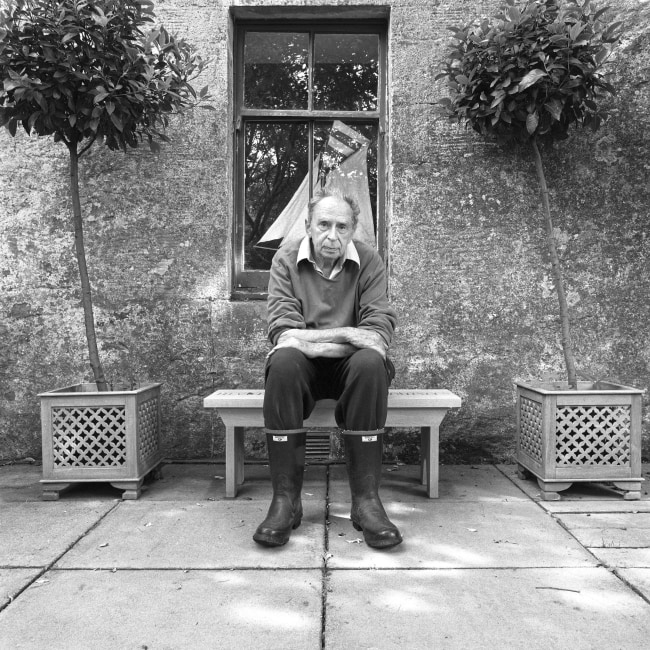

Alice Neel, Ian and Mary, 1971

-

![]()

Adriana Varejão, Monocromo Jiaguwen Azul, 2013

-

![]()

Suling Wang, Shadow Wing, 2013

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View

-

![]()

Installation View